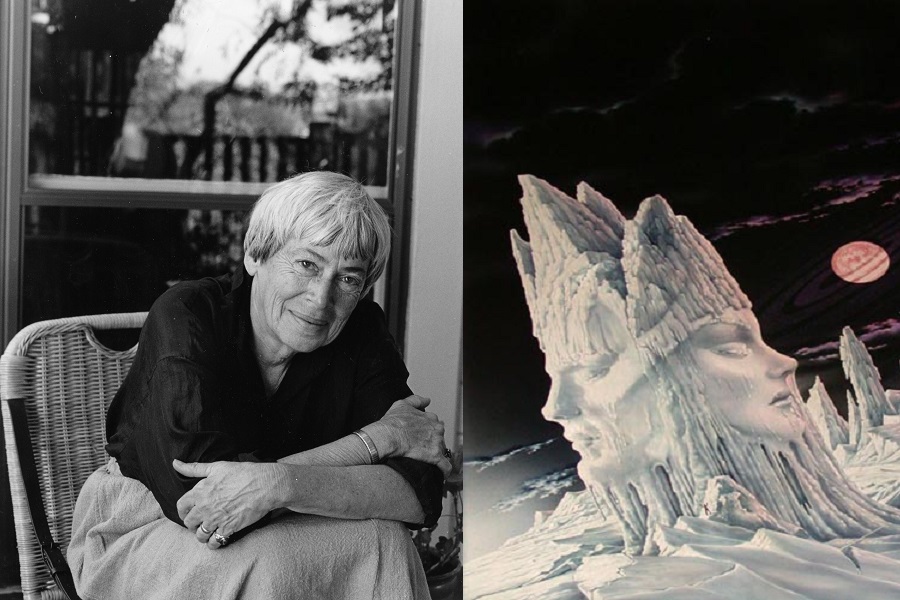

In her 1969 space opera The Left Hand of Darkness the author Ursula L. Le Guin has much to say about gender. Genly Ai, a diplomat from the planet Terran and our protagonist, is sent to the planet Winter to establish trade with its inhabitants. This alien species exists in a kind of sexual limbo. There is no gender. A man is a woman, a woman, a man, all at once.

Confused? So is Genly Ai. Haling from a planet resembling our Earth, Genly understands sex and gender both to be binary. As he is thrust into this genderless world, he finds himself excited, perplexed and most of all frustrated. His lack of understanding about these people and their strange, antiquated ways makes him a difficult perspective to sympathize. He is what modern readers would consider politically incorrect, obtuse, and at times downright rude, and so unapologetically male.

This work has been lauded over the years for its forward thinking about sex, sexuality and gender. In the end, though, I’m still not sure what Le Guin is trying to say about all of these. That is my greatest criticism about this book. She wrote a whole novel that seems to grapple with the issue of gender, yet her own opinions about the subject remain unclear.

As a 21st century kid, I can understand Le Guin’s being limited by language or even ignorance. She was writing in a different time, trying to project ideas that didn’t even have names yet. The word hermaphrodite is often used to describe the people of Karhide, and in today’s literature you simply wouldn’t see that word because it’s dated, rude.

But, it isn’t just her language that I had a problem with, it was her tone towards women, or rather, Genly’s tone.

Take, for example, our problematic protagonist Genly Ai. He often cites the Karhidians’ flaws as feminine or womanly. “But on Gethen nothing led to war. Quarrels, murders, feuds, forays, vendettas, assassinations, tortures and abominations, all these were in their repertory of human accomplishments . . . They lacked, it seemed, the capacity to mobilize. They behaved like animals, in that respect; or like women. They did not behave like men, or ants.” He refers to all of these creatures by masculine pronouns (he, him, his) even though they are clearly genderless. In his mind, he is constantly to categorize everybody he meets. The person to whom he gives his rent money every month is his “landlady” because they are described as having womanly hips. His companion Estraven is “he” because, well, he just is.

Le Guin’s novel is inarguably innovative, and undoubtedly it paved the way for more women in sci-fi. Still, the author’s treatment of gender and sexuality feels too far in the past for this reader.