Aatia Davison

Engl 146

April 28th, 2016

BOYD

Word count: 3, 082

Blessed are the Meek: Marginalized People in Women’s Dystopian

One of my most distinct memories is standing in line at Southpoint mall to watch the midnight premiere of the Hunger Games with my friend Hannah. The line wrapped all the way around the building. I can still feel the spring air light as a feather on my cheeks. The two of us were buzzing with anticipation for the big moment when we would see District 12 come to life. There have been so many films like it since, as there were books like it before. A fan myself, I have often wondered: why do we love dystopias? It is a question that we have been asking ourselves in this class for weeks now. What is it about this genre that hooks people. The books, the movies, the merchandise, the ideas. Why do they sell so well? Also, what does this genre’s success indicate about our own society?

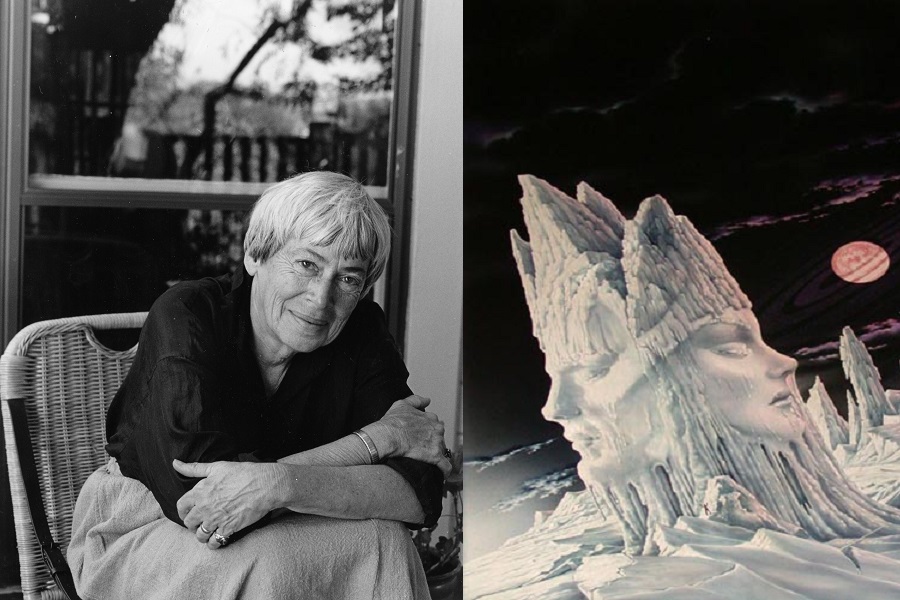

First, I think it important to define dystopian or speculative fiction. “A dystopia must arouse fear, but fails if it completely overwhelms the reader, leaving no room whatsoever for hope of amelioration” (New Dictionary of the History of Ideas). That is an interesting word choice, hope. In order to work, a piece of dystopian or speculative fiction must deal with the future, a reader’s anxieties and hopes for what is to come. Speculative fiction serves a purpose. According to Ursula K. LeGuin, “The purpose of a thought-experiment . . . is not to predict the future— indeed [it] goes to show that the ‘future,’ on the quantum level, cannot be predicted— but to describe reality, the present world. Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive” (The Left Hand of Darkness). It could be argued, however, that its purpose is to do both, to speak at once about the possibilities, as well as the present.

In this way, dystopian fiction has acted as an excellent vehicle for social justice and societal transformation. Many progressive, women writers like Octavia E. Butler, PD James, Margaret Atwood and even more recently Suzanne Collins, write for dystopian. It is, it would seem, a perfect match. “Centrally concerned with the clash between individual desire and societal demand, dystopian fiction often focuses on sexuality and relations between the genders as elements of this conflict” (Woman on the Edge of a Genre). Dystopian fiction also confronts modern clashes of race, class and disability as well as gender. It is a perfect platform on which to present these issues, as it capitalizes on society’s deep-seated fears and insecurities about the future— how will society progress? Or, like in the Handmaid’s Tale, Children of Men and the Hunger Games, how will society regress? Good dystopian fiction criticizes those in power by implying that their goals, and their expectations for the future are selfish, dated and even dangerous. This criticism is ubiquitous throughout the aforementioned works. That is why they are studied; that is why they are celebrated.

In her criticism of Children of Men, Susan Squier touches on how feminist science fiction can challenge certain archetypes. “As feminists, we are quite familiar with the problems bred by the nuclear family, from violence to agoraphobia. As feminist science studies scholars, we face a dilemma equally bred by that disciplinary nuclear family that can (at least for polemical purposes) be imagined as a choice between two directions” Feminist writings have to challenge old beliefs about wives and families because women have always been relegated to that family role. Male writers can only relate to them as part of a “family” if she is an individual, not grounded to a house or husband but allowed to roam free, she is a slut, a whore, or a bitch. Often feminist writing has to turn this idea on its head. Squier argues that “James’s (1992) novel is an important meditation on what development, growth, aging, and death might mean in a culture robbed of birth and childhood” (np). To be robbed of birth and childhood means to be robbed of hope for the future. What is significant about James’ writing though, is that she centers the story around a man in extraordinary circumstances, someone who has befriended a pregnant woman, someone with hope. That ties back into this idea that dystopian fiction cannot work if it leaves the reader entirely hopeless.

It is relevant to examine the cultural circumstances that created these works. Octavia Butler’s Kindred and Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale were published in 1979 and 1985 respectively during America’s resurgence of Conservatism. They both serve as responses to right-wing rhetoric that was being put out at the time. Nixon promised in his presidency to be “tough on crime,” declaring the “war on drugs” which we can now recognize as coded language. A more politically-correct way of saying we are going to police black people’s neighborhoods, criminalize their behavior, and imprison them in droves. This approach was popular among white southerners who were threatened by desegregation in the South. Butler manages to combat this in Kindred, a story featuring a black female protagonist romantically tied to a white man in 1970’s California. The Handmaid’s Tale was written in the aftermath of the Roe v. Wade decision and second-wave feminism wherein which women’s bodies and their right to choose were of great social moralistic concern. This conservative climate allowed for progressive movements such as feminism and racial equality to find their dystopian voices in contemporary issues. It would be a gross understatement to say that Roe v. Wade inspired Atwood to write The Handmaid’s Tale. Indeed it was a whole climate of fear for the future (from both the left and the right) that allowed for the authors’ speculations of what was to come. Writers like Atwood and James assessed their environments and wrote fiction that would mirror right-winged ideology in the worst way possible. They presented worst-case scenarios of white supremacy, oppressive patriarchies and crippling classism. They point to societies regression all on account of the greed and hate of those who were in power.

One could argue against the literary merit of The Hunger Games, but the fact is that in an MTV, Kardashian-crazed, video game obsessed social climate— one that relies so heavily on spectatorship, complacency, and the perverse glorification of violence— it is not hard to imagine Collins’ “not-too-distant future” as our own.

This all ties back in to Le Guin’s statement on this genre being more about the present than anything. Authors take the worst parts of humanity and condense them, centralize them to situate characters in climates of fear, and audiences are simultaneously fascinated and disturbed.

The future that feminist writers allude to is unanimously one lead by people belonging to marginalized groups. The disenfranchised, the meager, the meek, they are the key. The Handmaid’s Tale includes at the end some “historical notes” on the narrator’s account by an American Indian scholar from the year 2195. Gilead fell, and America’s Indigenous people have returned to power. In Children of Men, it is a group of disabled/deformed individuals, immigrants and people of color who challenge a tyrant. Society’s reject are the first to reproduce after two decades. In The Hunger Games, a girl and a boy from District 12, the poorest outermost district take down the President Snow and reunite Panem. These dystopias all suggest that hope, here meaning hope for a brighter future, lies with those who have been shut out, those on the fringes of society.

“When Omega came it came with dramatic suddenness and was received with incredulity. Overnight, it seemed, the human race had lost its power to breed. The discovery [took place] in July 1994 that even the frozen sperm stored for experiment and artificial insemination had lost its potency.” (Children of Men, 8) In the world of PD James’ Children of Men, the future looks bleak. There have been no births in twenty years and the world has all but given up on a next generation.

In Great Britain, the leader has capitalized on this lack of hope. The people’s listlessness has allowed him to create a society that will believe most lies, and justice the most heinous crimes. As Warden of England, Xan has created a supposed utopia. One with lower crime rates, less violence, less sexual imagery. People feel safe in their doom. “We are outraged and demoralized less by the impending end of our species, less even by our inability to prevent it, than by our failure to discover the cause. Western science and medicine haven’t prepared us for the magnitude and humiliation of this ultimate failure.”(Children of Men 5) There is an insane obsessiveness that Western culture has with the Omega phenomenon. It is a blow to their pride, a personal failing, that they, all of their seemingly infinite wisdom, cannot find the cause of the problem. They do not wish to solve it, but they want to identify a reason for their suffering. A reason. Western ideology puts an emphasis on the cause and effect relationship of things. The fact that their white, male-driven, Western, superior silence failed to predict this drives the country into its descent.

A clear sign that a cure is not on the top of the Warden’s list of priorities is the fact that there was “no interrace cooperation”(Children of Men, 6). If they had been so concerned with the well-being of their own people, James suggests, they would have crossed class, racial, or ableist boundaries to find a cure. After all, comes from a man and a woman who society has pushed out for their disabilities. Almost every one of the Five Fishes, Julian, Luke, Miriam, and Rolf, has something to offer in this respect— some sort struggle that has made them a pariah. Whether their “otherness” is defined by class, race or their disabilities, it is crucial that the solution comes from them, the outsiders, the meek. In her work the Human Project, author Jayna Brown agrees, “Racialized subjects, black and brown people, serve absolutely pivotal functions in a startling number of science fiction narratives, and particularly within post-apocalyptic worlds. Black characters determine the crucial meaning and messages of many of these narratives as they bear the weight of the apocalypse.They often hold the truths and the message of the films, often representing both the damning critique and its terms of vindication. [A person of color] literally holds the key to the survival of humankind,” (Human Project).

Brown also asserts that Children of Men in some ways predicted the future for Great Britain. “ In the late 1990s and early 2000s, these groups organized locally in European centers and came together for transnational actions, such as simultaneous demonstrations, supporting the rights of transnational “precarious workers” and against “migration management for a global apartheid regime,” as the Crossing Borders Newsletter wrote in 2008. “(Human Project) Children of Men spoke to very real anxieties that people had about immigration and changing demographics in the United Kingdom. Its deftness in criticizing conservative, racist policies make it a progressive work.

Theo is a compelling protagonist because he does not exist is either camp— insider or outsider. He is someone who, for all intents and purposes, could be considered on the inside given his familial connection to Xan and his socioeconomic status, but he is not. He has chosen to set himself apart, saying “I don’t want anyone to look at me. not for protection, not for love, not for anything.”(Children of Men, 26). His despondency about the world makes him, as far as he is concerned a blank slate. He notes that “as a historian, I see it as the beginning of the end” (Children of Men, 8) That is why he is so easily roped into the Fishes’ scheme. He is impartial.

Maybe impartial isn’t the right word. He is not impartial when it comes to Julian, to whom he is drawn in like a magnet, despite her deformity (and marital status). His love or lust for her, is a driving force in his part of the revolution. He is not impartial in his feelings toward Rolf, either, who he regards with contempt. Still, Theo is the perfect voice to hear this story from because he, like the readers, come to an understanding about the way things work from the outside. He gives people someone that they can relate to. Julian and her baby give him a sense of hope that empowers him. If youth equals hope, then Julian, too equals hope. Her name actually latin for youthful, and it is no coincidence.

Children as hope is a recurring theme throughout dystopian, women’s dystopian especially. In Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale, the Republic of Gilead has had fertility problems of their own. The ability to reproduce is something that is both revered and reviled. “One of them is vastly pregnant […] There is a shifting in the room, a murmur, an escape of breath; despite ourselves we turn our heads, blatantly, to see better; our fingers itch to touch her. She’s a magic presence to us, an object of envy and desire, we covet her. She’s a flag on a hilltop, showing us what can still be done: we too can be saved.” (Handmaid’s Tale, 61). Again, Handmaid’s Tale is a perfect medium to convey feminist ideology. Women bear the brunt of Gilead’s oppression. They are told what to wear, what to say, when to speak. They are divided up by class, but in the end, none of them have any power. “Sterile. There is no such thing as a sterile man anymore, not officially. There are only women who are fruitful and women who are barren, that’s the law.” (Handmaid’s Tale, 123)

According to David Ketterer, who wrote Margaret Atwood’s “the Handmaid’s Tale”: A Contextual Dystopia “Gilead is based on a new right-wing, religious fundamentalism. In this regard, Atwood’s choice of dedicatees for the novel is significant.” (np) It is, as the name suggests, the story of a woman who society has turned their backs on. She someone who comes back into her own sexuality “I would like to be without shame. I would like to be shameless. I would like to be ignorant. Then I would not know how ignorant I was.” (Handmaid’s Tale, 40) Because she is a woman, Offred takes on all of these titles and a number of abuses which become too much for her. The moment when she tosses them aside, she is empowered; she is in revolt. Offred’s voice as the narrator ties back into the important of marginalized voices, of the meek in dystopian. “This isn’t a story I’m telling. It’s also a story I’m telling, in my head, as I go along. Tell, rather than write, because I have nothing to write with and writing is in any case forbidden. But if it’s a story, even in my head, I must be telling it to someone. You don’t tell a story only to yourself. There’s always someone else.” (Handmaid’s Tale, 85)

To return to the idea of children as hope, Suzanne Collins The Hunger Games is the most literal interpretation of this idea. When Panem fell to the Capitol, the children of each district were offered up as a sacrifice, punishment for disobedience. “Taking the kids from our districts, forcing them to kill one another while we watch – this is the Capitol’s way of reminding us how totally we are at their mercy. How little chance we would stand of surviving another rebellion. Whatever words they use, the real message is clear. “Look how we take your children and sacrifice them and there’s nothing you can do. If you lift a finger, we will destroy every last one of you. Just as we did in District Thirteen.” (Hunger Games, 76) It is a physical act, to ship children off to the capitol to watch them die.

Where does hope come in? The fact that they are children is the glimmer of hope that all successful dystopias need according to the New Dictionary of the History of Ideas. They are young, impressionable, but characters such as Katniss and Rue and Primrose remain kind, brave and rebellious. The youth are the meek, and as a young person who overcomes the Capitol’s legacy of violence, Katniss Everdeen literally inherits all of Panem. Collins has chosen children to be her outsiders because they are always the victims of circumstance, with no voices with which to defend themselves. But, this novel also shows how children and hope can become corrupted. The kids from the inner districts are ruthless and brutal, killing for sport, and taking great pride in their victories. They are trained from birth to be smarter and better than the competition, blood-thirsty and psychotic like fighting dogs. Like PD James put it in her own work, “if from infancy you treat children as gods they are liable in adulthood to act as devils.” (Children of Men, 11)

Dystopian as a genre works as a platform for radical ideas about society’s values and its future. In order to work, there has to be a bit of light against the bleak backdrop of England, of Gilead, of Panem. That hope, in the cases of these three works, is children. To bring new life it to the world, is to change it altogether. For this reason, dystopian relies on them as symbols.

Only the marginalized person in dystopia inherits the earth. After dealing with oppression and violence to no fault of their own, only they have the ability to soberly assess society’s flaws and to start revolutions. “Without the hope of posterity, for our race if not for ourselves, without the assurance that we being dead yet live, all pleasures of the mind and senses sometimes seem to me no more than pathetic and crumbling defences shored up against our ruin.” (Children of Men, np.)

Works Cited:

- Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986. Print.

- Brown, Jayna. “The Human Project”. Transition 110 (2013): 121–135. Web…

- Collins, Suzanne. The Hunger Games. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print.

- James, P. D. The Children of Men. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1993. Print

- Ketterer, David. “Margaret Atwood’s “the Handmaid’s Tale”: A Contextual Dystopia (“la Servante Écarlate” De Margaret Atwood: Une Dystopie Contextuelle)”. Science Fiction Studies 16.2 (1989): 209–217. Web…

- Squier, Susan. “From Omega to Mr. Adam: The Importance of Literature for Feminist Science Studies”. Science, Technology, & Human Values 24.1 (1999): 132–158. Web…